While in-text citations are easy to do, they are often a lot more intricate than they first appear. While most students get to grips with using them quite quickly, this blog post is going to highlight some of the subtleties of in-text citations. This not only includes where they should go in your sentence, but some additional notations you can use depending on how you are using a reference. Whilst the examples below use Harvard/APA referencing, many of the principles are the same for footnotes.

The following six examples should help you get to grips with them:

1. Mentioning an author’s name in the text:

You are not limited to (Author, Date) citations in your writing. Where appropriate, you can also mention an author’s name in text. This can be used to vary your writing, but also allows you to make a clear attribution of an idea to its author(s).

According to Bartram (2018:56), the use of the term ‘presentation’ in relation to a PowerPoint file is problematic.

According to Bartram (2018:56), the use of the term ‘presentation’ in relation to a PowerPoint file is problematic.

Mentioning the author’s name in your text is also a great way to combine the definition of an abbreviation with a citation. For example:

According to the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC, 2018), there are multiple…

2. Being clear what text is cited and what is your own

When you write your paragraph, it needs to be totally clear to your reader which information is from your sources and which is from you. Consider the following excerpt:

Whilst the story itself can engage, there is also emphasis on the role of the presenter/storyteller as a performer. Presenters are encouraged to act out dialog, using different voices if possible, even moving from side to side on the stage to illustrate that different people are talking. This aspect of using stories in business presentations is perhaps one of the reasons why higher education lecturers have been uncomfortable with taking on the role of storyteller (Stevenson, 2008).

With the reference at the end, it is difficult to see which part of the writing is information from the source and which is from the essay writer. To solve this, always put your reference immediately after the cited information:

Whilst the story itself can engage, there is also emphasis on the role of the presenter/storyteller as a performer. Presenters are encouraged to act out dialog, using different voices if possible, even moving from side to side on the stage to illustrate that different people are talking (Stevenson, 2008). This aspect of using stories in business presentations is perhaps one of the reasons why higher education lecturers have been uncomfortable with taking on the role of storyteller.

You could make it even clearer by writing:

Whilst the story itself can engage, there is also emphasis on the role of the presenter/storyteller as a performer. Stevenson (2008) encourages presenters to act out dialog, using different voices if possible, even moving from side to side on the stage to illustrate that different people are talking. This aspect of using stories in business presentations is perhaps one of the reasons why higher education lecturers have been uncomfortable with taking on the role of storyteller.

Sometimes, putting the reference in the middle of the sentence is the best way to achieve clarity:

However, the importance of story within the business world, especially in advertising (Fog et al., 2010) and leadership culture (Tommi et al., 2013; Mead, 2014) means that it cannot be ignored within business education.

3. Using multiple references in the same sentence

As hinted at in the example above, when you are referring to multiple ideas in the same sentence, it is important to indicate which sources link to each idea. If we take the following example, it is difficult for your reader to see where these points originally came from:

These developments have become known not only as edge cities, but also as ‘suburban downtowns’ and ‘technopoles’ (Lee, 2007; Garreau, 1991; Hartshorn & Muller, 1989; Scott, 1990),

Below, we have placed the in-text citations, as close to the associated ideas or points as possible. It makes it a lot easier for the reader to see which source links to which point:

According to Lee (2007), these developments have become known not only as edge cities (Garreau, 1991), but also as ‘suburban downtowns’ (Hartshorn & Muller, 1989) and ‘technopoles’ (Scott, 1990).

4. Using secondary references

When you want to reference something cited, quoted or reproduced in another source, you need to use a secondary reference. An example of this would be seeing a quote from a book, cited within a journal article. In this case, you’ve read the article, but not the original book. Wherever possible, you should always use the original source. Secondary references are problematic as you cannot rely on the accurate interpretation by the writer. However, sometimes the original source is simply not available.

When you want to reference something cited, quoted or reproduced in another source, you need to use a secondary reference. An example of this would be seeing a quote from a book, cited within a journal article. In this case, you’ve read the article, but not the original book. Wherever possible, you should always use the original source. Secondary references are problematic as you cannot rely on the accurate interpretation by the writer. However, sometimes the original source is simply not available.

First, reference only the source you have read in your reference list. Next, you need to use your in-text citation to explain the original source and where you found it to the reader. This bit is important as you can use it to suggest the nature of the original source. For example, if it is a mere quote, or a full reproduction of the original. Here are some example phrases:

Harrison (2008) cited in Peters (2010) implied that…

Rebecca Bishop, a native American public relations officer (quoted in Sorensen, 2012) believes that…

In a letter to his brother, Rembrandt admitted his reluctance to accept money (Rembrandt, 1880 in Stone, 1995).

(Rorty interviewed in McReynolds, 2007)

5. Giving other directions in your brackets

You can add other information into your bracketed text too. Common examples of this would be:

(see also Brown, 2017)

(for more examples see Smith, 2011; Jones, 2014 and Wilson, 2017)

(for a more detailed account see Green, 2015)

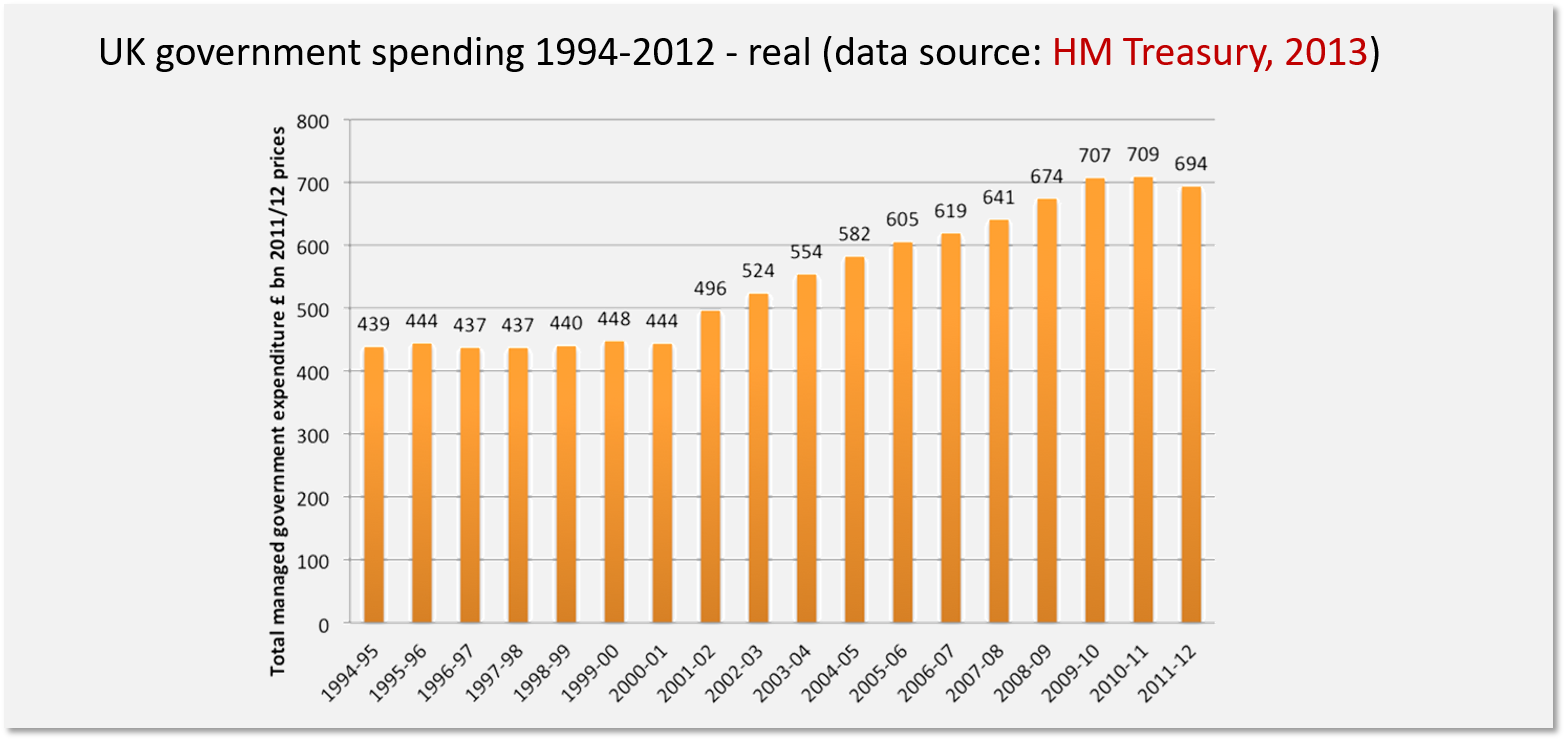

6. Indicating a data source used to create something

There are times when you create your own diagrams or charts using information or data that you have got from a different source. Even though the diagram/chart is your own work, you need to acknowledge where the original information/data came from:

Remember the overriding principle: make sure it is as clear as possible exactly what information came from which source – and which parts of your work are all your own.